|

Mind and Supermind

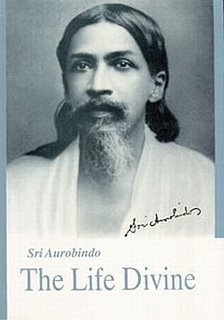

The paradise described in Semitic religions is an other-worldly affair and conceiving it to exist in the impurity of life would be a blasphemy! But in a similar vein, it is also difficult to envisage that a supramental living that manifests Sachchidananda in earthly life can be ever possible; rather it would appear to be ‘a state of being, a state of consciousness, a state of active relation and mutual enjoyment such as disembodied souls might possess and experience in a world without physical worlds, a world in which differentiation of souls had been accomplished but not differentiation of bodies, a world of active and joyous infinities, not of form-imprisoned spirits. Therefore it might reasonably be doubted whether such a divine living would be possible with this limitation of form-imprisoned mind and form-trammelled force which is what we now know as existence’ (The Life Divine, pg 172).

|

|

If we consider that this world of ours or in a way, the entire existence is a creation of God, then it would be difficult to conceive that paradise can blossom in the matrix of our existence as we know it, the two would remain eternally separate and the gap could be breached only after death and that too by chosen souls. Or else the world could be looked upon as an illusion, an ‘undivine Maya’ while The Absolute conceived positively as Sachchidananda and negatively as the Void was the only Reality with no ‘souls’ to be ‘chosen’ as the creation was transient and false! The whole vision can change if we consider that the creation is not merely a piece of exhibit that is displayed but a phenomenon ‘created’ within the very substance of God, a phenomenon pre-existent in the Divine artistry, ‘created not outside but in the divine existence, conscious-force and bliss, not outside but in and as a part of the working of the divine Real-Idea’(Ibid, pg 174). The creation is then no more the result of an illusory and undivine Maya but the working out of a supreme creative Idea (Real-Idea) through the guidance of the Divine Will, the higher Divine Maya.

As long as the creation was considered to be the result of an illusory undivine Maya, it was contemptuously marginalized to seek the Beyond-Maya Reality. The moment Sri Aurobindo advocates that the creation is a handiwork of the higher Divine Maya, it became obligatory to examine the relation between the undivine Maya and the Divine Maya which actually gives the clue to understand the relation between what is considered as the illusion and what is conceived to be the Divine Reality. As he admits the limitations of the tradition: ‘We have not scrutinized this other and apparently undivine Maya which is the root of all our striving and suffering or seen how precisely it develops out of the divine reality or the divine Maya. And till we have done this, till we have woven the missing cords of connection, our world is still unexplained to us and the doubt of a possible unification between that higher existence and this lower life has still a basis’ (Ibid, pg 173).

The link between the lower reality and the Divine Reality can be made if we consider that the principles of mind, life and body are ‘subordinate activities’ and ‘instrumentations’ arising from distortions and dilutions of the higher Divine principles. The distortion is not a freak or a mere aberration but a willed movement of the Divine Maya to create a world of multiplicity. The Supreme Existence (SAT), Conscious-Force (CHIT-SHAKTI), Delight (BLISS) and Supermind get distorted to be reflected in the subordinate principles that constitute our body, life and mind. This distortion was intended to create a variable world of forms. This is because in the Divine Consciousness, the higher principles exist as a single Reality conceivable in various poises but essentially indivisible and therefore incapable to manifest whereas in the world of creation, the oneness has to be sacrificed for divisible forms to provide uniqueness and variability. ‘But in reality all that we call undivine can only be an action of the four divine principles themselves, such action of them as was necessary to create this universe of forms’(Ibid, pg 174).

Momentous consequences follow. If the lower principles are subordinate activities of Divine principles that have become distorted and deviated ; they need not be ostracized but allowed to be transformed so that perfection can be achieved in life and paradise enacted in earth itself. ‘Mind, life and body must then be capable of divinity…They work as they do because they are by some means separated in consciousness from the divine Truth from which they proceed. Were this separation once abrogated by the expanding energy of the Divine in humanity, their present functioning might well be converted, would indeed naturally be converted by a supreme evolution and progression into that purer working which they have in the Truth-Consciousness. In that case not only would it be possible to manifest and maintain the divine consciousness in the human mind and body but, even, that divine consciousness might in the end, increasing its conquests, remould mind, life and body themselves into a more perfect image of its eternal Truth and realise not only in soul but in substance its kingdom of heaven upon earth’ (Ibid).

A camp of God is pitched in human time.

Savitri, pg 531

Date of Update:

23-Jul-16

- By Dr. Soumitra Basu

|