|

That 'real self' is not

affected by the pains and pleasures of our body, by the fluctuating

emotions of our vital or by the doubts and prejudices of our ideas

and premises. Indeed, if we can have the experiential contact with

one's inmost essence, one can remain 'detached' from the outer

disturbances that are possessed as passing 'experiences' which do

not overwhelm the individual.

The nature of this 'inmost

essence' or 'real self' is that of 'BLISS' – it is actually a 'Bliss

- Self' that radiates Ananda, love, joy, purity: 'In the entirely

expressive Sanskrit terms, there is an anandamaya behind the

manomaya, a vast Bliss- Self behind the limited mental self, and the

letter is only a shadowy image and disturbed reflection of the

former. The truth of ourselves lies within and not on the surface.'

(Ibid, pg115)

In subsequent chapters and

in numerous letters to aspirants, Sri Aurobindo explains how this

'real self' develops inside us from a soul- spark to the 'Psychic

Being' that itself is the projection of a Central Being or Jivatman

above the manifestation.

Now this 'real self' cannot

directly influence our outer being or surface personality. Its

influence can only be discernible if another dimension of being – a

new dimension of our personality develops. This is another unique

contribution of Sri Aurobindo to the world of Psychology. He names

it as the 'SUBLIMINAL' or 'INNER' Being that stands behind the outer

being. He gives a detailed description of the Subliminal in Book II

of the Life Divine explaining in details its difference from the

Subconscious.

The Subliminal or 'Inner

Being' is connected with the cosmic or universal consciousness. It

is through the subliminal that the universal delight in 'the

aesthetic reception of things as represented by Art and Poetry'

enter to influence our outer being, 'so that we enjoy there the Rasa

or taste' of the sap of Creation. That 'Rasa' or 'nectar' of

existence does not even exclude the taste of the 'sorrowful, the

terrible, even the horrible or repellent'. That is why Shakespeare's

tragedies are as important as his comedies, and Kali's wrath can be

as beautifully portrayed as Krishna's love. That is why Michael

Angelo's David can be beautiful even after killing the demon and the

nailed body of Jesus is a source of compassion, not of vengeance. It

is interesting to note that the 'sorrowful', the 'terrible', the

'horrible' sensations have been depicted in Indian Art in the famous

forms of Karuna, Bhayankara and Bibhatsa Rasas, and these are as

important as their opposites.

The 'Subliminal' as a

gateway to Universal Delight

The

outer being revolves around the ego and is too 'divided' to receive

the impact of the Universal Delight. The subliminal is under the

influence of our 'real self' and is not biased by the ego. Hence it

can receive the Universal Delight as 'an aesthetic reception', which

then percolates into the outer being. This 'percolation' of course

depends on the level of development of the outer being – on its

finesse and receptivity, on its 'culture' and 'education'.

One must be cautious that

the mere aesthetic reception of the Universal Delight in existence

through our subliminal does not automatically qualify that the

'Ananda' of Sachchidananda has been perceived. To perceive that

'pure-delight' which is 'supramental and supra-aesthetic', the inner

being has to progress considerably, so that its upper realms extend

into the 'superconscious'. Indeed, the inner subliminal can extend

into the 'superconscious' as well as plunge into the 'subconscious'

enroute the 'Inconscience'. 'Certainly, this aesthetic reception of

contacts is not a precise image or reflection of the pure delight

which is supramental and supra-aesthetic; for the latter would

eliminate sorrow, terror, horror and disgust with their cause while

the former admits them: but it represents partially and imperfectly

one stage of the progressive delight of the universal Soul in things

in its manifestation and it admits us in one part of our nature to

that detachment from egoistic sensation and that universal attitude

through which the one Soul sees harmony and beauty where we divided

beings experience rather chaos and discord. The full liberation can

come to us only by a similar liberation in all our parts, the

universal aesthesis, the universal standpoint of knowledge, the

universal detachment from all things and yet sympathy with all in

our nervous and emotional being.' (Life

Divine, Pg. 119)

'Ananda' or 'Bliss'

supports the entire creation

We have discussed that

'Ananda' or 'Bliss' is the only answer to the 'Why' of existence.

But then, this is something that can only be realised at a very high

superconscient plane. Does it really support the entire field of

creation? Or is it something that exists in isolation at the highest

planes of consciousness?

Sri Aurobindo explains that

though it is 'realizable' at a very high plane of consciousness, its

presence is 'discernible' throughout existence.

'It is the reason of that

clinging to existence, that overmastering will-to-be, translated

vitally as the instinct of self-preservation, physically as the

imperishability of matter, mentally as the sense of immortality

which attends the formed existence through all its phases of

self-development and of which even the occasional impulse of

self-destruction is only a reverse form, an attraction to other

state of being and a consequent recoil from present state of being.

Delight is existence, Delight is the secret of creation, Delight is

the root of Birth, Delight is the cause of remaining in existence,

Delight is the end of birth and that into which creation ceases.

“From Ananda,” says the Upanishad, “all existences are born, by

Ananda they remain in being and increase, to Ananda they depart”.'

(Life Divine, Pg. 111)

Sri Aurobindo's

uniqueness in the description of Ananda?

Traditionally, the 'Ananda'

or 'Bliss' poise of Sachchidananda has been experientially perceived

at a very high superconscious level. The Bliss could not be brought

down to our egoistic life, as it would have been disruptive. That is

why our 'heavens' have been located in superconscient spheres, far

above ordinary life. Of course, different spiritual paths have

'constructed' their 'heavens' with the different types of

superconscient experiences with which they contacted the 'Ananda'

poise of Reality. To some, it represented 'Rapture', to some it

represented 'love', to some it was 'Peace', to some it represented

'Beauty', to some it represented 'Silence'. Accordingly the

'heavens' have been named in the Indian tradition by different

names. Sri Aurobindo explains that wherever the knowledge in man

leads him to think it can grasp this bliss, 'it will fix its

heaven.' 'This is Swarga, Vaikuntha, Goloka; this is Nirvana'

(Essays Divine and Human, Pg. 216).

To Sri Aurobindo, the key

word is 'transformation' of our existence so that the

'Superconscient' experiences can manifest in material life. Our

heavens have to blossom not in very high realms but in this

apparently mundane life. That is why is emphasized the discovering

and developing the 'Real Self' within us, which in its nature

radiates 'Bliss'. Sri Aurobindo ventures to suggest that if

developed, this 'Real Self' can come forward as a fourth dimensional

principle and replace the ego. This sounds preposterous but there is

a way for that journey. If the ego can really be 'replaced' by the

'Real Self' in ordinary existence, then only the heaven of 'Bliss'

can manifest in our earthly life. Of course, this means working on

our own selves and developing our 'subliminal' or 'inner being'

behind our surface personality. Psychology becomes a gateway to

Spirituality. One has to work not only at one's 'heights' of

consciences but also at one's 'depths', complementing each other.

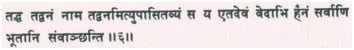

'DELIGHT' IN THE UPANISHAD

“The name of That is the

Delight; as the Delight we must worship and seek after It”

(Kena Upanishad, 1V.6))

This Upanishadic sloka

(couplet) describes Brahman in its poise of transcendental Delight.

It is the All-Blissful Ananda from which all existences are born, by

which all existences live and increases and into which all

existences arrive in their passing out of death and birth. This is

the 'immortality' of the Upanishads. The soul, which is identified

with this Bliss, can be one with the infinite existence and yet in a

sense still able to enjoy differentiation in the oneness. In other

words, that soul becomes a centre of the divine delight – a fountain

of joy and love to which all fellow-creatures can be attracted.

(Source: Sri Aurobindo, The Upanishads, Pg. 181)

[However, as explained above, such a soul described in the Upanishad

that radiates a fountain of joy is still a soul that realizes Ananda

in the superconscient plane of existence and attracts souls who have

set out for that 'ascent'. Sri Aurobindo wants a 'descent' of the

Ananda or self-existent Delight in ordinary existence – a unique and

utopian vision waiting for fulfillment.]

Date of Update:

22-Jun-13

- By Dr. Soumitra Basu

|