|

The Divine Soul

The limitations of the human soul

The Supreme Consciousness in its existential mode is present as an essence as a self or soul-element in each form. Undeniably, of all forms in the present manifestation, the human form is the most conscious, developed and responsive and thus the human soul has a chance to manifest the latent powers and potentialities of the Supreme Consciousness. Yet there are two cardinal reasons for which the ordinary soul cannot reveal the effulgent Splendour and Power of the Supreme Consciousness. Firstly, at the level of the manifestation, the human soul finds great resistance from the saga of Falsehood and Ignorance that veils it triumphantly. Secondly, the intellect can give a metaphysical construct of the Absolute but does not convey an experiential realization or revelation. ‘The intellect tells us simply that there is a Brahman higher than the highest, an Unknowable that knows itself in other fashion than that of our knowledge; but the intellect cannot bring us to its presence’(The Life Divine, pg 165).

|

|

If we observe carefully, the limitations of the human soul expressed in its inability to burst the veils of Ignorance and Falsehood and it its inability to surmount the shortcomings of the intellect; both stem from one common source which lies in the phenomenon of the multiplicity of the manifestation getting disconnected from the inalienable unity that is the sine qua non of the Supreme Consciousness. The difference between the inalienable unity of the Supreme and the endless divisibility and variability of the manifestation is difficult to be bridged even in metaphysical quest, so much so, that the difference has been alluded as an inexplicable illusion, a veritable Maya.

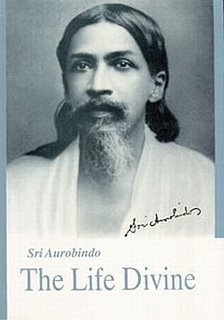

For the first time in metaphysical and spiritual history, Sri Aurobindo bridged the gap between the One and the multiplicity by his revelation of the Supramental Consciousness that is poised between the Absolute and the manifestation, carries the pre-programmed essence of creation and moves towards the manifestation in a graded way where more the multiplicity is revealed, the more the Unity is concealed. As a result, the multiplicity does not become merely a phenomenon divorced from the unity-principle but both the unity and the multiplicity together constitute the ‘SELF-MULTIPLIED IDENTICAL’ (Ibid, pg 164).

The acknowledgment that the multiplicity of the manifestation and the inalienable Unity of the Supreme Consciousness are not two dissociated phenomena, one signifying inexpressible Infinity and the other signifying an expressible limitability but poises of a single Reality has enormous bearings in constructing a fresh world-view. However such a world-view cannot be constructed from the ordinary poise of the human soul in the manifestation. There is a psychological as well as a metaphysical reason for this difficulty:

(a) Psychologically, unless the separatist egoism is dealt with, one cannot have a glimpse of the unitary consciousness.

(b) Metaphysically, a mere abolition of the ego leads one to an experience of the Absolute where the multiplicity becomes ephemeral and non-existent.

Sri Aurobindo therefore postulated that after abolition of the ego, if the soul can be poised at the Supramental Consciousness where unity and multiplicity are simultaneously tangible realities, then a truly integral world-view could be constructed. Chapter XVII of The Life Divine deals with such a poise which he termed as that of the Divine Soul.

‘Moreover, such a divine soul would live simultaneously in the two terms of the eternal existence of Sachchidananda, the two inseparable poles of the self-unfolding of the Absolute which we call the One and the Many. All being does really so live; but to our divided self-awareness there is an incompatibility, a gulf between the two driving us towards a choice, to dwell either in the multiplicity exiled from the direct and entire consciousness of the One or in the unity repellent of the consciousness of the Many. But the divine soul would not be enslaved to this divorce and duality. It would be aware in itself at once of the infinite self-concentration and the infinite self-extension and diffusion. It would be aware simultaneously of the One in its unitarian consciousness holding the innumerable multiplicity in itself as if potential, unexpressed and therefore to our mental experience of that state non-existent and of the One in its extended consciousness holding the multiplicity thrown out and active as the play of its own conscious being, will and delight. It would equally be aware of the Many ever drawing down to themselves the One that is the eternal source and reality of their existence and of the Many ever mounting up attracted to the One that is the eternal culmination and blissful justification of all their play of difference. This vast view of things is the mould of the Truth-Consciousness, the foundation of the large Truth and Right hymned by the Vedic seers; this unity of all these terms of opposition is the real Adwaita, the supreme comprehending word of the knowledge of the Unknowable’ (Ibid, pg 166).

‘All earth shall be the Spirit’s manifest home..’ (Sri Aurobindo, Savitri, pg 707)

Date of Update:

19-Feb-16

- By Dr. Soumitra Basu

|